What if Flawed was a Flex?

Our society values the newest, shiniest objects. “New” once meant that you were wealthy. You could afford ready-made clothes, for example, by incurring costs for both materials and labor involved, rather than purchasing materials and completing the work yourself. Those store-bought clothes were a luxury, a status symbol.

Ready-made items are no longer more costly. Buying materials and tools required for a maker hobby, be it sewing, furniture building, or art, is more expensive than buying an item brand new.

Why is it so cheap to have ready-made objects?

Because of globalization and exploitation of people overseas. Slaves. Items are made in mass scale by miserable people in dangerous work environments who couldn’t care less for the quality of the item that you receive because they aren’t being cared for adequately to create it.

This is the norm. People are enslaved so that those who place “shopping” at the top of their hobbies list can sip sugary lattes with no whip and stroll casually through Target, placing items in a still-rolling red basket without a second thought. Everyone wants something new. Advertisers in their past and influencers in their present have convinced them that they will be hotter, happier, admired, and have better sex if they buy specific items.

Overworking to Overconsume is not a Flex

In the past, our capitalist overlords wanted us to buy in to the idea that more is better, that your displays of wealth will impress your neighbors. Wealth is either inherited or worked hard for, so copious amounts of consumer goods, luxury, or knock off trophies express that you were the hardest worker or that you were born on third base. Either way, you “won” at having money.

What I’ve seen is a shift in our society. People are awake, aware that overworking for a class of people that don’t care about their well-being isn’t worth it. Most are overworked, underpaid, and at what cost? To afford another knock off item shipped from overseas? Why work harder so the guy spinning his pen in the corner office can make the most money?

People now are more concerned with quality of life. “Most money” isn’t the only game to play. The McMansion is dying. They want more time with their friends and families, less square footage to prove to their grade school bully that they’re worthy. They want to pursue hobbies that they love, they want fulfilling lives outside of work.

What if it was Different?

What if wanting something shiny, new and unblemished was no longer the baseline? What if, instead, people began to see the beauty in the story of imperfect items? What if the crookedness of a hemline wasn’t a bug, but a feature to announce that you were the creator of the item?

What if having a flawed, self-made item was a signal to the viewer that stated: “I have values outside of material trends. I have time and patience to learn a new skill and complete the task poorly, as a beginner. I get satisfaction out of learning and doing that outweighs that of overwork to purchase something pristine.”

Patina

Years ago, I was brushing turquoise paint into the crevices of a newly bought metal door knocker. My husband looked at me quizzically, asked me what I was doing. I shared with him that when something of this metal ages, it begins to change to this color. It’s added character, added beauty, that comes only with age. I was painting the item to imitate that look.

“It’s called patina.”

He latched on this word, to this concept. When I show concern for something getting bumped, mangled, stained, run into by the kids, his reply has consistently been a simple shrug and the word “Patina.”

When I hear “Patina,” my tightened muscles and gritted teeth go lax. I take a deep breath, my tongue drops from the roof of my mouth, my agitated heart begins to slow. Because it’s true. A ding on an item is a story, just like a scar on your body. Body positivity teaches us to accept our imperfections, to love the body we were given, to see our stretch marks from pregnancy as “tiger stripes.” What if we were to do the same with the items we own, the homes we live in? What if we were to embrace them, not in spite of their flaws, but because of their flaws—because the stories they hold?

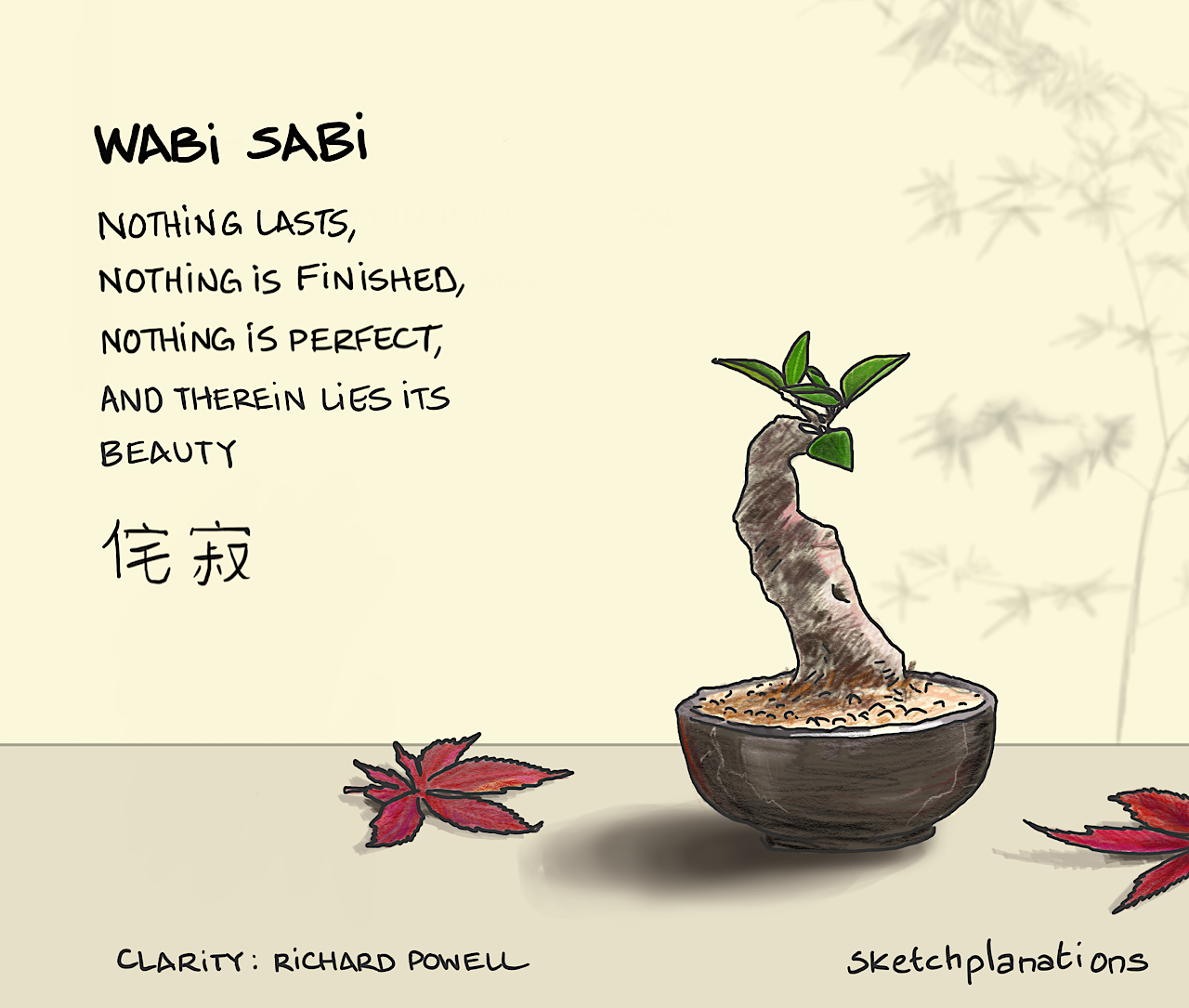

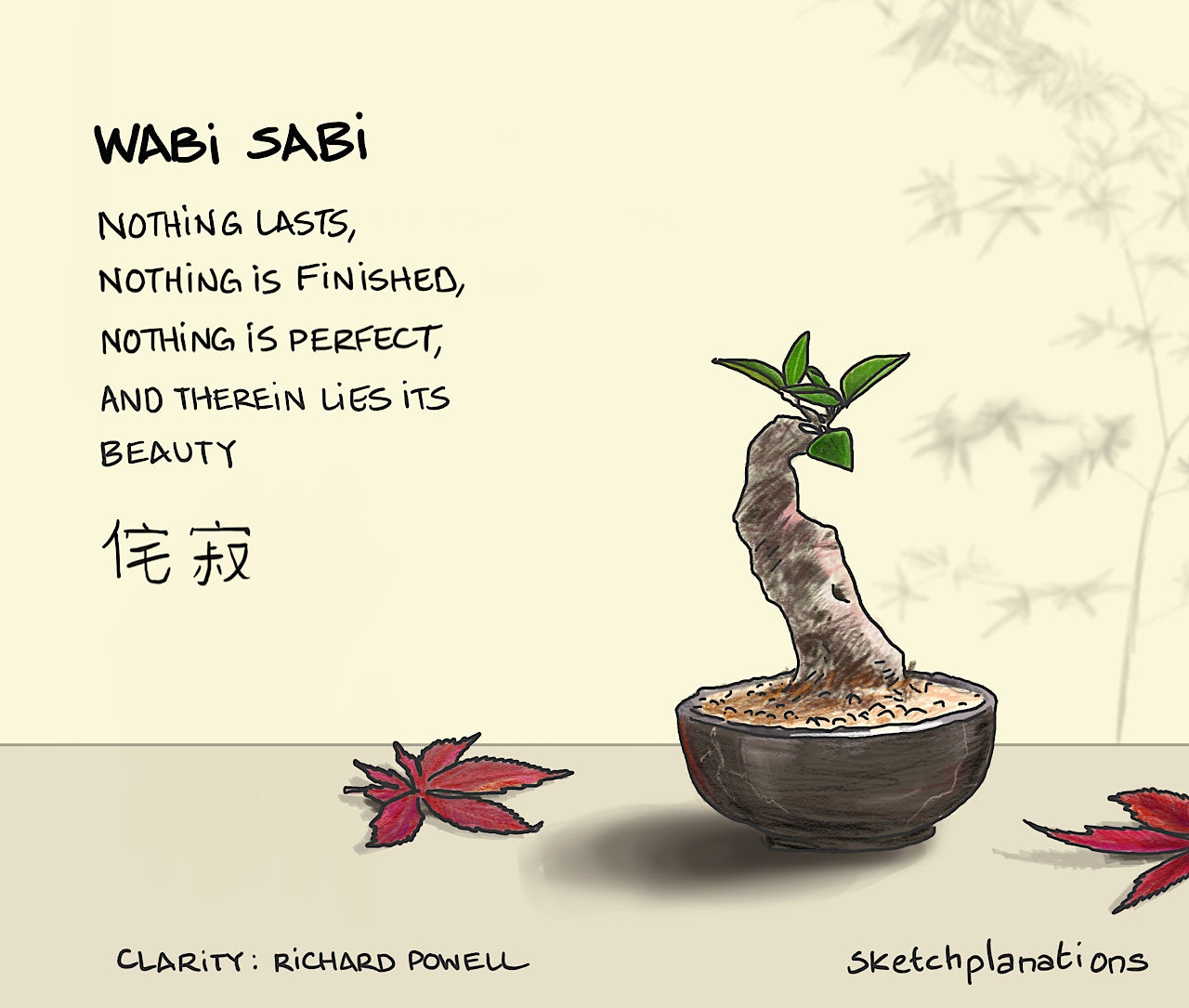

Wabi-Sabi

Wabi-Sabi is a Japanese concept that was introduced to me through a children’s book. Yet, it’s not simple to define like China’s Yin-Yang. Like Africa’s Ubuntu, this Japanese concept, wabi-sabi, can’t be directly translated into a word in English.

Sketchplanations

Many boil wabi-sabi down to seeing the beauty in imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete, and accepting the natural cycle of growth and decay.

Wabi-sabi is tricky to grasp. Apparently some Brit went so far as to creating a whole docuseries to understand its essence. In Wabi-Sabi: For Artists, Designers, Poets & Philosophers, it seems that this is by design:

Some Japanese critics feel that wabi-sabi needs to maintain its mysterious and elusive—hard to define—qualities because ineffability is part of its specialness. […] missing or undefinable knowledge is simply another aspect of wabi-sabi’s inherent “incompleteness.”

Leonard Koren, Wabi-Sabi for Artists, Designers, Poets & Philosophers

Wabi-sabi is the moment when you see that daub of yellow paint on the ceiling, and instead of feeling exacerbated by “needing to fix it,” because its flaw, you see it as a feature, a reminder of when you stood atop a ladder with a paintbrush taped to a broom handle and did your best. It’s basking in the joy of your long list of creative projects, not rushing to complete all of the tasks because nothing is ever complete.

Even in death, there is no completion. Rotting and decay become nutrient-rich soil that nourishes mycelium and plant life that sustains animals once again.

Wabi-sabi doesn’t exist in an item, even if it falls under the categories that many use to describe the aesthetic. Wabi-sabi only exists for the moment it’s being experienced. Once you move your thoughts away from appreciating a wilting flower, it is not wabi-sabi anymore. Wabi-sabi is just as impermanent as the materials it describes.

Changing Perceptions of Beauty

The future of our species would be lengthened and enhanced if we created new associations around beauty. Waste in landfills would reduce if we stopped throwing away items because we couldn’t see beauty in their degradation with normal wear and tear.

After reading Nature’s Best Hope, I learned how removing leaf litter and suburbia-approved lawn practices are devastating to the ecology. Among the sources I read after that initial book, one wrote that regarding fall cleanup of leaf litter and trimming of stems on wintering plants, to reconsider what is beautiful. We’ve been conditioned to perceive only a neat yard as beautiful, but what of those crunchy, cream colored spent hydrangea bulbs in mid February? Is the hiking trail in December, covered in the same leaves that fall in your yard, not beautiful? Allowing my leaf debris to stay throughout the winter, for the sake of the pollinators, required a lesson in new associations.

The same can be done for aesthetics within the home. I can drop my perception of what things should look like and know that my items aren’t reflections of my worth based on their perceived cash value, but rather a reflection of the values that I live by.

The Hem is Crooked

…but I did my best at a skill that is new. What does the crooked hem say about me?

“I have values outside of material trends. I have time and patience to learn a new skill and complete the task poorly, as a beginner. I get satisfaction out of learning and doing that outweighs that of overwork to purchase something pristine.”

What do you think?