Paris 1874

I am glad this was asked today as my kids head back to school after the holidays. There was a similar prompt that I began writing right before school let out that I didn’t manage to complete.

What was the last thing you did for play or fun?

Holiday madness and extreme expectations that fall upon women at this time of year are upon us. That, partnered with some scary events for loved ones have made this week a particularly tough one. I try to have fun in all that I do: getting dressed and cleaning included, and exercise, like kicking the ball back and forth with my son in the morning while we wait for the bus.

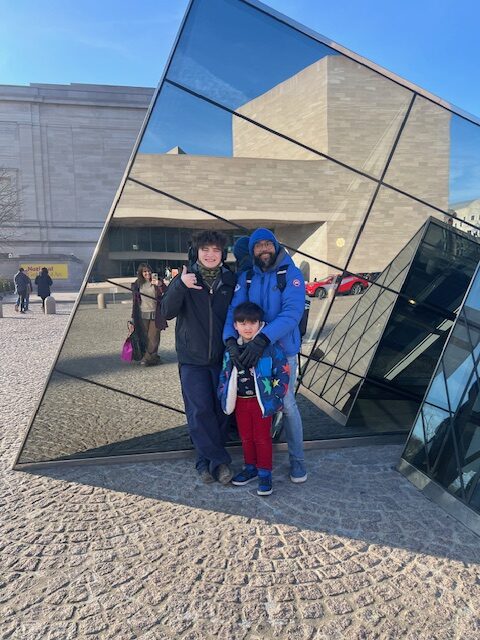

The last time I did something just for pleasure wasn’t over a century ago, as this blog title alludes. Rather it was last weekend, when I went on a road trip to Washington D.C. for a once-in-150-years exhibit about the impetus of the Impressionist art movement. The title of the exhibit was Paris: 1874.

Now I know that you’ve seen an impressionist painting or two, artist or not. Long past the point of copyright, prints of Monet’s are for sale on any surface imaginable.

Myth of the Impressionists

If you’ve taken a couple of art classes, you may have come across the myth of the Impressionists: they were shunned from being shown alongside more popular works of the time, deemed not “good enough” in quality, so they went on to form a separate show. You may have even heard that “Impressionist” was a name derived from an insulting journalist reporting on the works exhibited as I did in my first painting class as an adult.

After viewing the Paris:1874 exhibit, I have different interpretations of the events that transpired.

Paris: 1874 at The National Gallery of Art

This sesquicentennial exhibit is unlike any preceding it, as it displays the impressionist works alongside the art that was accepted in the Salon from which they were rejected.

Société Anonyme was the name of exhibit of the impressionist works that preceded the traditional Salon. The artists planned for the show to take place prior to the opening of the Salon so that it would not be perceived by the public as a collection of works that were rejected, though that was the case.

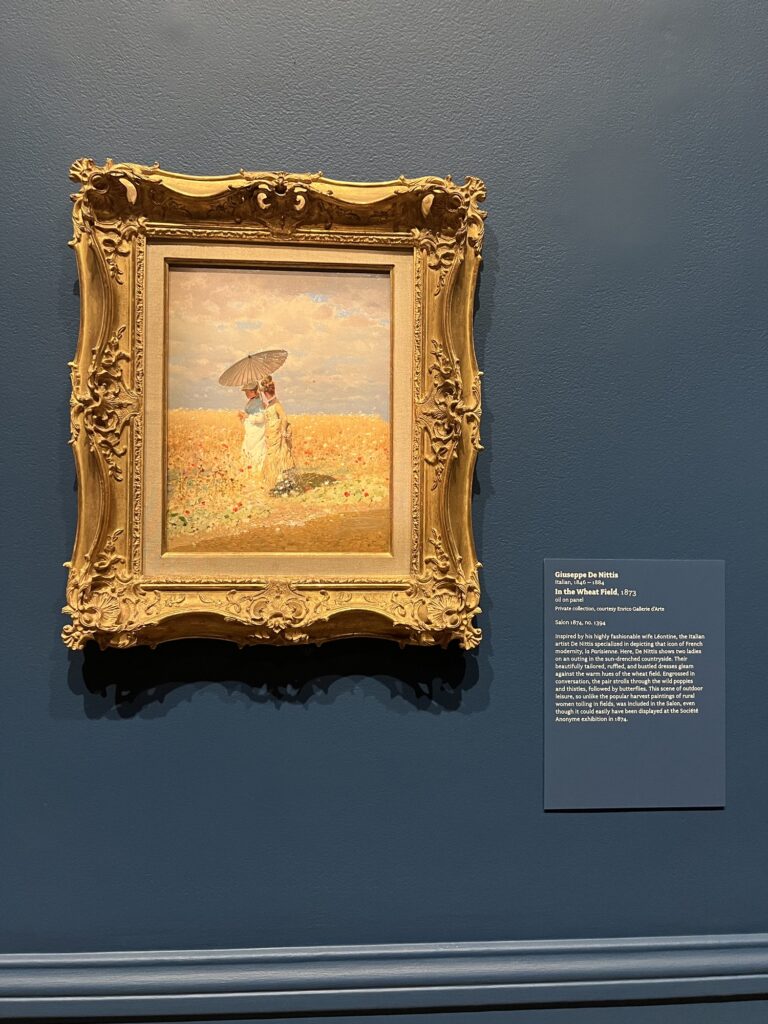

These artists weren’t rejects across the board—many had works that were successful in previous Salons or were showing other works in the Salon that year. Impressionism as a style was beginning to gain some footing. The following two paintings were accepted into the Salon, both of which share elements that are similar to those whose work is deemed “Impressionist.”

War & Tragedy Leading to the Salon of 1874 & Introduction of the Impressionists

The exhibit introduced me to fascinating history surrounding the time period. Three years prior to the Salon and the Société Anonyme (“Impressionist”) exhibits, Paris was fraught with war, destruction, and political turmoil. Working men partnered with veterans from the recent Franco-Prussian war to revolt against oppressive leadership, and succeeded.

The Paris Commune

The government established following the fall of France’s Second Empire was too similar to the monarchy, too conservative, and did not align with the views of the people. The Paris Commune, the name given to those in revolt (though they were not limited to Paris), chased the government out of the city to Versailles with canons left behind from the preceding war. When the generals came to seize the canons with their armies, troops refused to fire upon the civilians and instead turned on both generals, who were beaten and shot to death.

The people ruled.

The Paris Commune of 1871 stood on a platform that included:

- Separation of church and state

- Free public education

- women’s rights

- labor rights (child labor laws, banned night shifts for apprentice bakers, set wages for civil servants that aligned with the average wage)

- limits on landlords and creditors

- fixed price for bread

- return of pawned items

This was a government by the people, for the people. It lasted for three months.

Then bloodshed ensued.

The Bloody Week, or semaine sanglante began May 21, 1871. There were between 10,000 and 15,000 dead, and buildings burned throughout Paris, including those of historical significance.

In 1874, many ruins from the tragedy remained. Parisians went about their day-to-day tasks with a backdrop of death and destruction resulting from their government.

Depicting History at the Salon

The most favored works of the Salon which the Impressionists were “excluded” from were those with historical ties, including those pictured below.

Though these works depicted scenes with a historical context, it wouldn’t be a stretch to assume that these works were simultaneously commenting on more recent events, closer to home, in a way that would be less dangerous than full on free speech against a government that has proven itself to be ruthless against rabblerousers. I could see how artists would be able to see themselves and other Parisians in works that depict mourning for soldiers going off to war, or being duped with a trojan horse, or in the varied expressions of mourning in Lawrence Alma-Tadema’s The Death of the Pharaoh’s Firstborn Son.

Walking through Paris: 1874

I’m getting sleepy, so I’ll try to wrap this up for us.

Outside of the exhibit, there was ample room to line and wait for entry into the exhibit.

It was good for crowd control, which was only an issue in the first room, and the line went by quickly.

While in line, there were projections of Paris in 1874: photographs that had been made into video through use of AI. This was a cool way to use the technology that even I can get behind: it gave the line an other-worldly feel that transported the visitors 150 years in the past.

The front room introduced the aforementioned political turmoil, set the stage, and explained the prestige of the Salon of 1874. And, of course, it featured the painting that inspired the name of the movement: Impression: Sunrise by Claude Monet.

I’m wrapping this post up, as I’ve had a long day.

After completing the exhibit, I stumbled on this guide who was giving a tour of the impressionist works outside of the exhibit to give visitors a greater understanding of the movement. Then I followed them around until he was done.

This is where he was when I came across him. The painting to the right of him, The Artist’s Garden at Vetheuil by Claude Monet, 1881 hung up in my apartment as a child. Perhaps its no coincidence that my love for impressionism is so strong.

Primary Takeaway from Paris: 1874

I’m a lover of impressionism of the highest order-my art style is primarily influenced by the original Impressionists. Imagine my surprise when I found that many of my favorite paintings in the exhibit were those that were selected by the Salon of 1874!

Impressionists were highlighting the everyday, which is important, and I love the subject matter of the movement just as I do the brushstrokes and saturated colors. Impressionists were also choosing compositions that intentionally cut out the ruins that surrounded the everyday. They were painting a pretty picture for the bourgeois and omitting the reality of what surrounded them. Focused on their salad, if you will.

Many of those selected for the Salon had a bit more story, more consideration in all of the objects and scenes depicted. They were telling a whole story in an image, while impressionists were showing a feeling or an essence.

It doesn’t mean one is better than the other. Space in any gallery is limited.

What interests me is this myth that has formed around Impressionism’s birth. People were already painting and exhibiting in this style, already getting into the prestigious galleries. The first impressionist gallery was seen by few and little was said about it by critics, that at that time, erred on extravagant roasting. Somewhere along the line, an underdog myth was adopted toward impressionists that elevated it higher. It reminds me of how I found out Thomas Edison didn’t really invent the lightbulb, he just had the best PR team.

Monet and his squad had a damn good PR team, too.

What do you think?